Space debris can endanger spacecraft and damage satellites that are critical to everything from communication to GPS, air traffic control, surveillance and national security.

By Robert Wells | October 13, 2022

Space may seem infinite but the real estate in Earth’s orbit is filling up fast with junk.

The debris orbiting the Earth consists of human-made objects that no longer serve a purpose and range from fragments of metal to nonfunctioning spacecraft and abandoned rocket stages.

This space junk can endanger spacecraft and damage satellites that are critical to everything from communication to GPS, air traffic control, surveillance and national security.

And despite space debris becoming a large and growing problem, public awareness about it has been understudied. That’s why University of Central Florida researchers are part of a new NASA-funded project to find out what people know about the topic and discover ways to make them care.

The findings will be used to help engage the public, which can influence policymakers to address the issue, the researchers say.

“The public needs to understand this issue because ultimately NASA and other government agencies in multiple countries are going to need to work together to address it, and we need voters who are informed to support these efforts,” says project co-investigator Phil Metzger ’00MS’05PhD, a planetary scientist with UCF’s Florida Space Institute.

Space debris could also impact the prospect of space tourism, says Sergio Alvarez, an assistant professor in UCF’s Rosen College of Hospitality Management and project co-investigator.

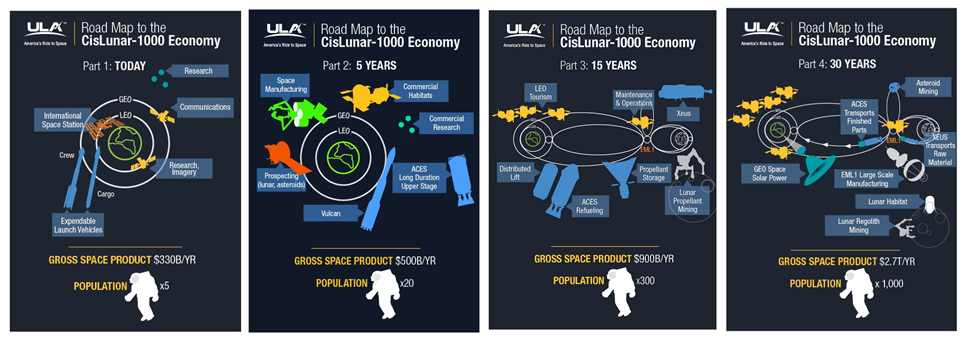

“Economic activities in Earth’s orbit are threatened by large amounts of human-made debris orbiting our planet and moving at very high speeds, in essence becoming deadly projectiles that can harm or destroy satellites, stations, ships or other infrastructure in Earth orbit,” Alvarez says. “So orbital debris poses an existential threat to the emerging industry of space tourism.”

Alvarez will help study the public’s willingness to pay for fixing the problem.

The researchers say addressing orbital debris issues could make some satellite-based services, such as internet and streaming television, more expensive due to pre- or postlaunch fees to cover satellite removal.

The one-year project will consist of interviews, a nationally representative survey and the testing of different messages related to framing space debris as an issue. NASA awarded $100,000 for the project, and it is one of three projects the agency recently funded to study orbital debris and space sustainability.

“Orbital debris is one of the great challenges of our era,” says Bhavya Lal, associate administrator for the Office of Technology, Policy, and Strategy (OTPS) at NASA Headquarters in Washington in a recent press release. “Maintaining our ability to use space is critical to our economy, our national security, and our nation’s science and technology enterprise.”

The project will be led by Patrice Kohl, an assistant professor of environmental communication at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry.

“There’s very little known about public familiarity, understanding and attitudes about space debris,” Kohl says. “Knowing key vocabulary around the issue, ways to frame it and what people already know will help us better communicate about the risks. There is remarkably little research in this area, and we hope to start filling in some of those gaps.”

Metzger received his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering from Auburn University and his master’s and doctoral degree in physics from UCF. Before joining UCF in 2014, he worked at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center for nearly 30 years.

Alvarez received his doctorate in food and resource economics from the University of Florida and joined UCF in 2018. He is a member of UCF’s National Center for Integrated Coastal Research and Sustainable Coastal Systems faculty research cluster. Between 2013 and 2018, Alvarez served as the chief economist at the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.